Antwerp QC, Much of Belgian Core, Leaves Competitive Quidditch

By Grace Dastous, Guest Writer

Editor’s Note: At time of press, the IQA membership department had not responded to requests for statistics or estimates of gender distribution in the league. As such, this article will focus on quidditch in the U.S. The author, Grace Dastous, is a chaser, president and coach for the Boston Pandas. Dastous has spent the last few months researching and working with women and individuals outside of the gender binary to create this piece. If you would like to comment or discuss the issues addressed in this piece further, you can reach her at gracedastous1@gmail.com.

“Non-male” is a gender identifier with no place in quidditch. It perpetuates the idea that genders are defined by male status.

USQ* estimates that its members–which includes players, snitches, referees and volunteers–are 50 percent men, 40 percent women and 10 percent identify outside the binary, according to USQ Executive Director Mary Kimball. MLQ’s 2019 player stats, according to the MLQ People Operations Department, shows a distribution of 69 percent males, 29 percent females, .70 percent non-binary, .23 percent agender and .23 percent genderfluid.

These statistics show quidditch, while not overwhelmingly so, is a male-dominated sport in the U.S., and because of this, people who do not identify as male endure many things on and off the field that many male-identifying athletes may not understand. One of these unique experiences is the use of the term “non-male.” While it is difficult to identify the true origin of the term non-male in quidditch, it’s important to note gender has always been a key component. The USQ Rulebook states that there can only be four of one gender represented on the field at once (excluding snitch play, when it becomes five). While the original intent was to ensure inclusion of females and those outside of the gender binary, in most situations present day–though not all–this leads to four men in play. The other two spots have become, over time, categorized as “non-male” positions, not just in discussion of rules but in everyday conversations about our sport.

In American Quidditch Discussion and other online forums, the term “non-male” is commonly used, not only by males, but females and those that identify outside of the binary. Jackie Ross, a feminist and member of our community, created a podcast called “What’s Next?” with the aim of discussing active change in our sport, including the empowerment of female and other marginalized players. However, even the word “non-male” crops up, conversationally, in a number of episodes. MLQ Commissioner Amanda Dallas commented publicly that she has used the term for years. Roarke McAllister was a guest in Matt Dwyer’s “HOMES at Home” episode 6 podcast, titled “Gender Studies.” During this discussion, McAllister, who identifies as non-binary, discussed their problem with the vocabulary of the “male line” and “female line” and previously felt as though the term “non-male” was the best descriptor of the group of people who did not identify as male. Dwyer, a long-time and well-known USQ volunteer, believed it to be the universal term in quidditch. These points and more act as a true testament to the colloquial spread of the term. I do believe that when people are using the term “non-male” they are, in actuality, trying to be inclusive while also not presuming someone’s gender. However, when this term is used, it, in fact, creates another binary system that we were all trying to avoid. As mentioned previously, it perpetuates the idea that genders are always going to be defined by male status.

This binary–male or other–leads to another common expression that holds heavy implications: “____ is such a great female/non-male player.” In episode five of Ross’s podcast, “The Male Perspective on Feminism in Quidditch with Joey Galtelli,” Ross invites long-time friend and player Galtelli to discuss actionable steps that team leaders can take in order to empower athletes that identify as female and outside the gender binary. One suggestion proposed was the elimination of the back-handed compliment “____ is such a great female/non-male player.” Why is it so difficult for people to just say “_____ is a great player”? Men seem to escape a “male” identifier, yet women and those that identify outside of the binary are often complimented as being a good “non-male” player. Why is there a completely different category for these athletes? Female players, players who identify outside of the gender binary and gender non-conforming players should be judged by their skill on the field. As previously mentioned, of the ~3,500 registered in USQ, approximately 50 percent are male, 40 percent are female and 10 percent identify outside the gender binary. Are Kaci Erwin, Lulu Xu, Lindsay Marella, Hallie Pace, Jules Baer and Bailee Fields really only better than the “non-male” athletes, which consists of ~2,000 players? Or can they compete with the other 2,000 male athletes in quidditch? These back-handed compliments not only occur in-person but also on AQD and other social media platforms. While these commenters–predominantly men–may have good intentions, the simple phrase of “non-male” implies that females and those that identify outside of the binary are not in the same category as a man, when, in fact, many of these athletes are better than a large percentage of male players. They’re on the same field. They’re in the same category.

In an effort to address the gender imbalance in MLQ gameplay leadership, MLQ’s former Human Resources Director Lisle Coleman conducted a gender inclusivity survey in 2018. The respondents were 93 percent female/woman identifying with an additional 11 respondents identifying as gender non-conforming. The results showed 84 percent of respondents had experienced gender-based discrimination. Of the 17 individuals who noted on the survey that they felt comfortable coaching, eight agreed that “my gender affects my decision to apply to be a coach.” While most respondents cited a lack of skill or knowledge, almost half of the individuals who were comfortable coaching chose not to apply not because of what they were lacking, but because of their gender identity. In an effort to address this discrepancy, MLQ enacted the Coleman Clause, a new hiring policy that actively seeks out more coaches that identify as female or outside of the gender binary.

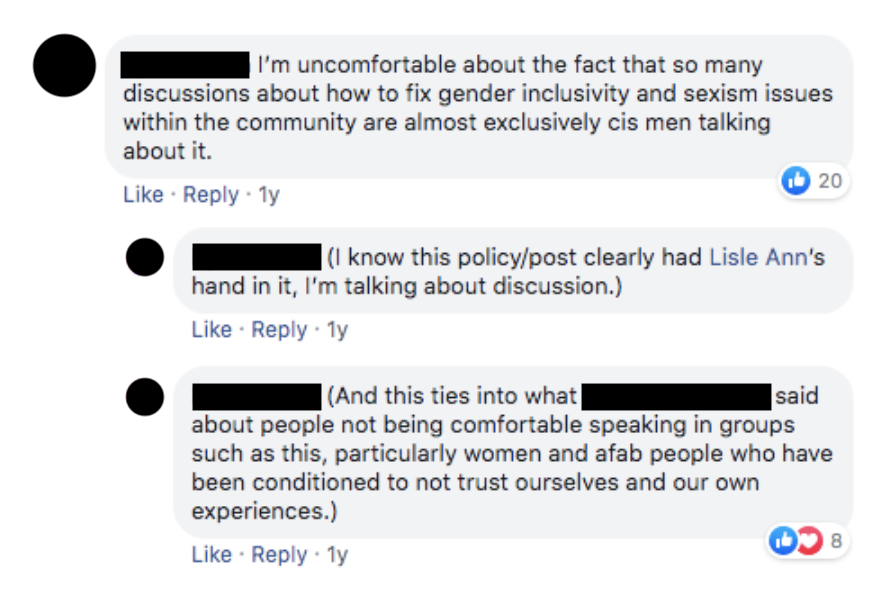

In AQD, this sparked debate. In the 122 comments that followed, gender identifiers such as “female,” “non-binary,” “agender” or “transgender” were not used once. The word “non-male” was used 15 times. As mentioned earlier, the intent of this survey was to address gender imbalance, yet, here we see that exact imbalance taking shape in a discussion about the survey specifically meant to address such.

MLQ’s gender survey participants were majority female or individuals that identify outside of the binary; they felt comfortable taking an anonymous survey, and yet were nervous to discuss gender discrimination publicly on the forums. Which begs the question, how can we encourage other voices beyond cis men to join the conversation? When we do hear from those who identify outside the binary or women, they tend to be members of status within the community, many of whom are respected for either athletic ability and/or logistical prowess. This indicates a need to prove oneself before feeling they’ve earned the right to speak–even more troubling when considering the paucity of women leaders or leaders who identify as outside the binary. It ties into the very reasoning behind the Coleman Cause.

As a result of MLQ’s new rule, five female coaches were hired in 2019. In 2020, this increased to 11 female coaches and one agender coach. In a 2019 celebration repost of this MLQ announcement in AQD, it was stated that “we now have four (4) new non-male coaches!” Obviously this individual, who was not a member of MLQ staff, was trying to commend Coleman and MLQ and praise the females that are now coaching; however, this fell short with another use of the “non-male” descriptor. If you are in a position in which you do not know a person’s gender, it is understandable to avoid an assumptive term such as “female.” “Non-male,” however, has nearly eradicated “female” and/or “woman/women” from our vocabulary in quidditch discussions. In a situation in which gender is known, it is okay to say the word female, non-binary, agender, bigender, etc. Doing otherwise perpetuates the idea that male is the only gender worth mentioning.

Another instance that was particularly shocking came on International Women’s Day 2019, when MLQ congratulated and celebrated “female coaches in MLQ as well as the non-male players and volunteers who contribute to this sport.” Instead of using the term “non-male,” MLQ should have acknowledged and celebrated women and those outside of the gender binary who wished to be recognized on International Women’s Day. Not all individuals who identify outside of the gender binary are comfortable being included in a group with women. To recognize those individuals outside of the gender binary, as was the initial intent of the 2019 MLQ post, organizations should also have a separate post for International Non-Binary Day on July 14, Agender Visibility Day on May 19, etc. There is no reason why the post on International Women’s Day could not have exclusively been about women or feminine-aligned people. Fortunately, we saw MLQ pivot in this direction for their 2020 season.

I understand, because of the USQ Rulebook, why we have moved toward grouping these communities together, but on a day that is about women, it is OK to use the word “woman.” On a day that is about non-binary individuals, it is OK to say “non-binary” and so forth. These words should not be feared. While this may seem small, the fact that that 2019 post came from MLQ, an organization that has done so much for females and individuals that identify outside of the binary, is indicative of how prevalent this problem is in our community. “Non-male” should not be the norm. We need to build a community where acknowledging one’s gender, accepting another’s gender and being open to having a conversation about gender should be the norm. Avoiding the topic and using the term “non-male” has been a trend that has been occurring for far too long.

MLQ and Coleman have also previously used the term “gender minority,” which is an attempt as not defining individuals by male status. “Gender minority,” seems to be a short, easy-enough phrase that all genders can use to describe the two players filling the gender requirement for a team. It also defines this group without using the word male as a descriptor. However, it still presents a couple of problems. Firstly, it lumps everyone into an “other” category, which then leads to gender being ignored entirely. The term “gender minority” alludes to minority gender groups in our world as a whole. By lumping females into this category, it takes away from the discrimination actual minority genders endure in everyday life, not just in quidditch. Secondly, some teams may have a majority of female players. In this case, the term would not be appropriate for these teams, but only for the community as a whole. Lastly, it groups people who may not identify or present as female into a category that is a majority female.

This season, however, the MLQ Marketing Department clarified the internal ruling that the league’s staff and volunteers needed to make a conscious effort to stop using the phrase “non-male,” substituting the term for “female” or the known gender of the person(s), “gender non-conforming” and/or “those that identify outside of the binary” dependent on the circumstance. This change acknowledges that the term “non-male” is problematic and furthermore demonstrates that MLQ is an organization that strives for gender inclusivity. A couple of different solutions have been proposed and discussed.

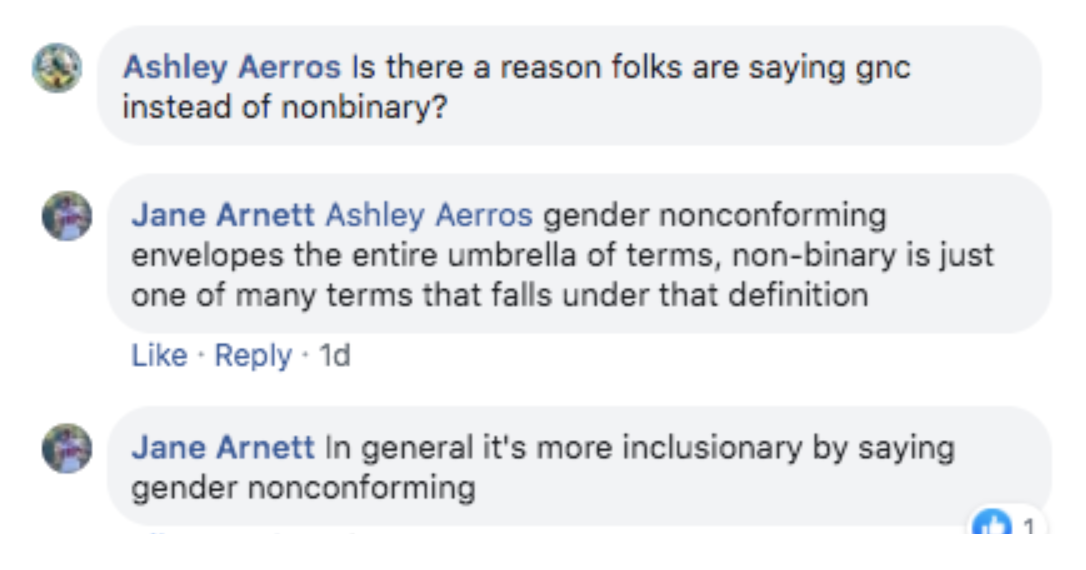

Another problem occurs with the phrase “female and non-binary individuals.” Although the term non-binary itself is an umbrella term for genders outside of the binary, some individuals are not comfortable with the term “non-binary” as an umbrella term and would prefer either a more specific or a more general term. A solution to this problem would be to start saying “female and gender non-conforming people.” Originally, this seemed like a good substitute for the term “non-male” and “gender minority.” To everyone’s credit in AQD on a discussion post about 3-3, most people stopped using the term “non-male” after Dallas’ comment about the alternatives: “female and gender non-conforming” or “those that identify outside of the binary.” As Jane Arnett, who identifies as non-binary, explained, the term gender non-conforming is an umbrella term that includes other genders and non-binary individuals and one they feel is more inclusionary than non-binary.

Also in this discussion, Ra Hopkins explains that “gender non-conforming” is a general term that includes those that identify outside of the binary but could also refer to cis people who may even partially present as the other binary gender (i.e. a cis male who wears nail polish). In this case, it may not refer to the group of individuals who are filling the gender requirement for a team. That being said, the phrase “those that identify outside of the gender binary” seems to be the most appropriate phrase at the given moment. Like McAllister and Dwyer discuss in the “HOMES at Home” podcast, the term “non-male” was brief and easy to say, whereas these longer phrases are more inconvenient. Unfortunately, there is no “perfect” phrase or term yet. McAllister, Dwyer and many on the forums do agree, however, that “non-male” should not be an option anymore.

The way that quidditch is structured currently, the terms “male” and “non-male” can almost be substituted for “privileged” and “unprivileged,” based on the male-dominance of the sport. The quidditch community simply needs to change its language by adding a few more words to a sentence in order for the “unprivileged” group to feel safer and able to express themselves and their true identities more freely. This adjustment would go a long way towards acknowledging the females and those outside of the gender binary who are on these teams or reading the posts online.

Although I have spoken to some people who identify outside of the gender binary about this topic, I do not presume to speak for that community. I urge those that identify outside of the binary and other females to speak out about how this language affects their confidence in the sport, but, even more so, I urge those in a place of privilege to ask questions, research, try to understand and stand up for females and those outside of the gender binary. Hold your friends, teammates and even your acquaintances accountable. Instead of saying “non-male” in order to avoid making assumptions about a person’s gender, have an actual conversation with others and ask about preferred terminology. I believe that this simple change in language could make a lot of people feel more comfortable with what is said in the forums and feel more accepted in everyday life in quidditch.

* USQ is currently working on a method of collecting more accurate numbers in relation to athlete gender distribution. The league also announced in February that Brandi Cannon would move to the role of Diversity and Equity Coordinator. MLQ also has a current opening for a similar role.

Archives by Month:

- May 2023

- April 2023

- April 2022

- January 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- July 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- August 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- November 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Archives by Subject:

- Categories

- Awards

- College/Community Split

- Column

- Community Teams

- Countdown to Columbia

- DIY

- Drills

- Elo Rankings

- Fantasy Fantasy Tournaments

- Game & Tournament Reports

- General

- History Of

- International

- IQA World Cup

- Major League Quidditch

- March Madness

- Matches of the Decade

- Monday Water Cooler

- News

- Positional Strategy

- Press Release

- Profiles

- Quidditch Australia

- Rankings Wrap-Up

- Referees

- Rock Hill Roll Call

- Rules and Policy

- Statistic

- Strategy

- Team Management

- Team USA

- The Pitch

- The Quidditch Lens

- Top 10 College

- Top 10 Community

- Top 20

- Uncategorized

- US Quarantine Cup

- US Quidditch Cup