Antwerp QC, Much of Belgian Core, Leaves Competitive Quidditch

Credit: Isabella Gong

Dear Community Teams,

You no longer matter to USQ. You are a minority, an afterthought, a sacrifice.

And that is exactly how it should be.

You had no business playing against college teams at regionals or nationals these last two years. You have turned into regional super teams with rosters chock full of some of the sport’s biggest and brightest stars, players who were at the core of the sport’s transition from whimsy to violent, from between-class fun on the quad to semi-professional, sponsored athletics. You amass talent at a rate that puts the Golden State Warriors to shame and you do it without a salary cap, free-agency restrictions or NCAA regulations. You can–and you do–take who you want, when you want, from where you want. You lure them in with veteran leadership, immediate competitiveness and no academic hoops to jump through.

Let me be clear in stating that there is inherently nothing wrong with any of the above practices. The only issue is that your college competition is not allowed these same freedoms. They can’t recruit from a 100-mile radius of ex-players, but rather a few square miles of a campus consisting of people completely new to the sport. Does their recruiting class of some 20-odd 18-year-olds really compare to your five recent graduates who started all four years on their college team? If I gave you even three fairly athletic freshmen and told you to have them ready to play significant minutes at your upcoming regional championship, do you think you could do it? Keep in mind your regional is actually the last weekend in October, so with their labor day start date, you have seven weeks to recruit them, run them through a tryout and train them. Oh, and you have to tell them they will miss their first Halloween weekend at college. Don’t forget the $60 upfront just to play for USQ, not to mention jerseys, cleats, mouth guards and any other equipment they’ll need. Good luck.

At its core, USQ is best equipped to handle a college-only league. Beyond the competitive imbalance, community teams bring in a whole slew of other issues counterintuitive to USQ’s focus to build and grow the sport. You 24-year-olds are a liability nightmare waiting to happen for these universities. When Sally’s mother finds out she tore up her knee on the school-sanctioned team not against another college player, but a full- grown, ex semi-professional linebacker, who do you think she’s going to go after to get those medical bills paid?

There is also the public relations issue of a mixed league. When trying to market the league to external sponsors, which hypothetical lede sounds better?

“Last season, University of Texas beat UCLA in a thrilling contest, with senior captain Lenny Hilton catching the winning snitch in his final match with the team.”

Or,

“Last season, the Lost Boys took down the Forgotten Ones in a memorable match that saw recent transfer Dustin Hogart, on his sixth team, score his first career hat-trick.”

Granted I have cherry picked a bit here to make my point, and “Quidditch Club Boston beats Rochester United” doesn’t really sound that bad. Yet, a casual observer still has never heard of these teams, whereas nearly anyone can quickly digest a rivalry between the public universities at our country’s two most populous states, with potentially intriguing sub-plots abound.

While the partial split (regionals and nationals) hasn’t solved every issue laid out above, it is a good first step and allows for some exciting compromises and new opportunities. Strong college programs can still test their mettle against their more-experienced community counterparts in official games counting toward their standings, earning both valuable and strength-of-schedule-boosting experience. And those college programs in a rebuilding year don’t have to see their new players demoralized in the first few weeks of their career in a 300*-20 blowout at the hands of a reigning regional champion community team. Tournaments, bemoaned of late for their lopsided and outdated group stage to bracket play model, could instead field two actually competitive subsets, without the stigma that comes attached with calling them Divisions I and II.

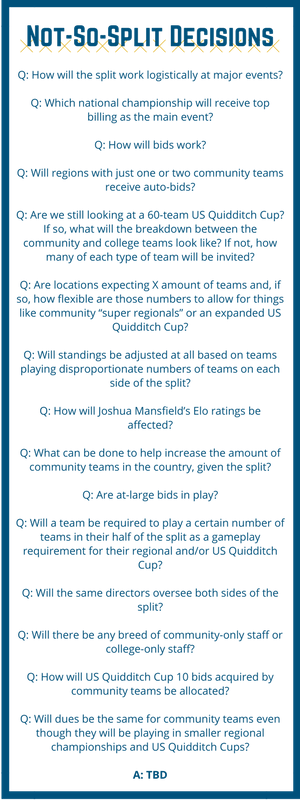

With all that being said, the split does disproportionately hurt community teams, which is going to be a point of much contention in the next few months. While some–particularly those in highly-concentrated regions like the West and South–will be in a position similar to this year, others–like those in the Midwest, Northwest and Great Lakes–will basically have no one to play against at regionals. With the announcement that team and player dues will remain the same–which totals to $1,400 for a 20-person roster–what are these teams really getting for their money?

With all that being said, the split does disproportionately hurt community teams, which is going to be a point of much contention in the next few months. While some–particularly those in highly-concentrated regions like the West and South–will be in a position similar to this year, others–like those in the Midwest, Northwest and Great Lakes–will basically have no one to play against at regionals. With the announcement that team and player dues will remain the same–which totals to $1,400 for a 20-person roster–what are these teams really getting for their money?

Bluntly, the answer is nothing. Let’s take the Northeast, where there were four community teams at regionals last year, excluding those college teams masquerading as community. Of those, three made the Elite Eight at US Quidditch Cup 10 and the other has won two combined games the past two seasons. Why on earth would Q.C. Boston, Rochester United and the BosNYan Bearsharks all spend $1,400 to play each other maybe twice at a USQ-hosted regional when they could easily do a double or triple robin-style tournament during the fall for pennies on the dollar. Then they could travel to a pseudo nationals, in the mold of the Bat City Invitational, sometime in early spring, using travel costs they would already have budgeted for USQ Cup.

The mold is already in place for how a community team’s season should go (hint: there have been games in this mold every weekend this summer) and the impetus is now on the leaders of the relevant community teams to forego USQ and make their own way. If you got me 20 teams, each paying $400 ($20 a person) as a tournament fee, I sure as hell could put on a national tournament spanning two days some weekend in late winter or early spring in a warm weather, centralized, major hub destination. And my name isn’t even Beth Peavler. You give someone like her those parameters and I guarantee it will be the a huge success. She has already proven that she can smoothly run a national tournament that draws well and provides good competition, and that’s with those teams who are at the bottom of the competitive spectrum. Imagine what could be done with the top 20 community teams?

So how do we make this happen? While it is ultimately up to the leadership of each team to decide what type of season serves them best, the ideal first step is for someone to come forward to organize such a tournament as spelled out above. While community teams still have months before they need to decide if they will go official or not, I have a feeling that the choices of the biggest teams–if made early enough–will definitely influence the others. Call it free market quidditch if you will, but I think an early decision by even five of the top community teams to break off and form their own national tournament is in their best interest, and that the others will follow, or not, as they see fit.

I ultimately don’t want to see college and community teams completely separated. I think it would be best for the sport as a whole to have them in different leagues under one governing body or in separate seasons. Yet, as the structure currently stands, the USQ fall-to-spring model is best served for the college teams and is not applicable to most community teams when there aren’t even 50 of us. I hope USQ recognizes this and continues to promote and grow the college league, while letting us find our own way, because the future of the sport depends on it. Community teams are overwhelmingly made up of post-grad players, and if that pipeline were to dwindle, it would adversely affect us too. We have a symbiotic relationship, and this will continue until college quidditch is no longer the competitive beginning of the sport. As members of community teams, our best interests lie in a strong, separate college league, because with it we will get a new batch of seasoned recruits every year.

Credit: Jessica Jiamin Lang

That being said, we must do our part. There are specific guidelines allowing coaches between divisions this season and we absolutely must use them. Offer to coach your alma mater and restore it to past glory, or at least back to qualifying for nationals. Open up your practices to the local college kids once or twice a month, and show them advanced strategy, and what high-level quidditch looks like from the same side of the pitch, not the other. Volunteer at the college-only regionals and nationals. Some of the best referees and snitches reside within the community team portion, and, without them, the college side will be severely under-staffed.

Yes, this is the beginning of the end for USQ-sanctioned community team quidditch. And that’s a good thing, because we already have a summer league with a much better model for a smaller number of teams in place from which to build. We go as college teams go, and if we want to still be playing this sport in even three years, we need to do our part to embrace this change, help it strengthen the sport’s base and think outside our immediate boxes, both geographically and time-wise. This is a step in the right direction and it is on us, the community teams, to determine how big of a step forward it is.

Archives by Month:

- April 2025

- May 2023

- April 2023

- April 2022

- January 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- July 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- August 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- November 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

Archives by Subject:

- Categories

- Awards

- College/Community Split

- Column

- Community Teams

- Countdown to Columbia

- DIY

- Drills

- Elo Rankings

- Fantasy Fantasy Tournaments

- Game & Tournament Reports

- General

- History Of

- International

- IQA World Cup

- Major League Quidditch

- March Madness

- Matches of the Decade

- Monday Water Cooler

- News

- Positional Strategy

- Press Release

- Profiles

- Quidditch Australia

- Rankings Wrap-Up

- Referees

- Rock Hill Roll Call

- Rules and Policy

- Statistic

- Strategy

- Team Management

- Team USA

- The Pitch

- The Quidditch Lens

- Top 10 College

- Top 10 Community

- Top 20

- Uncategorized

- US Quarantine Cup

- US Quidditch Cup